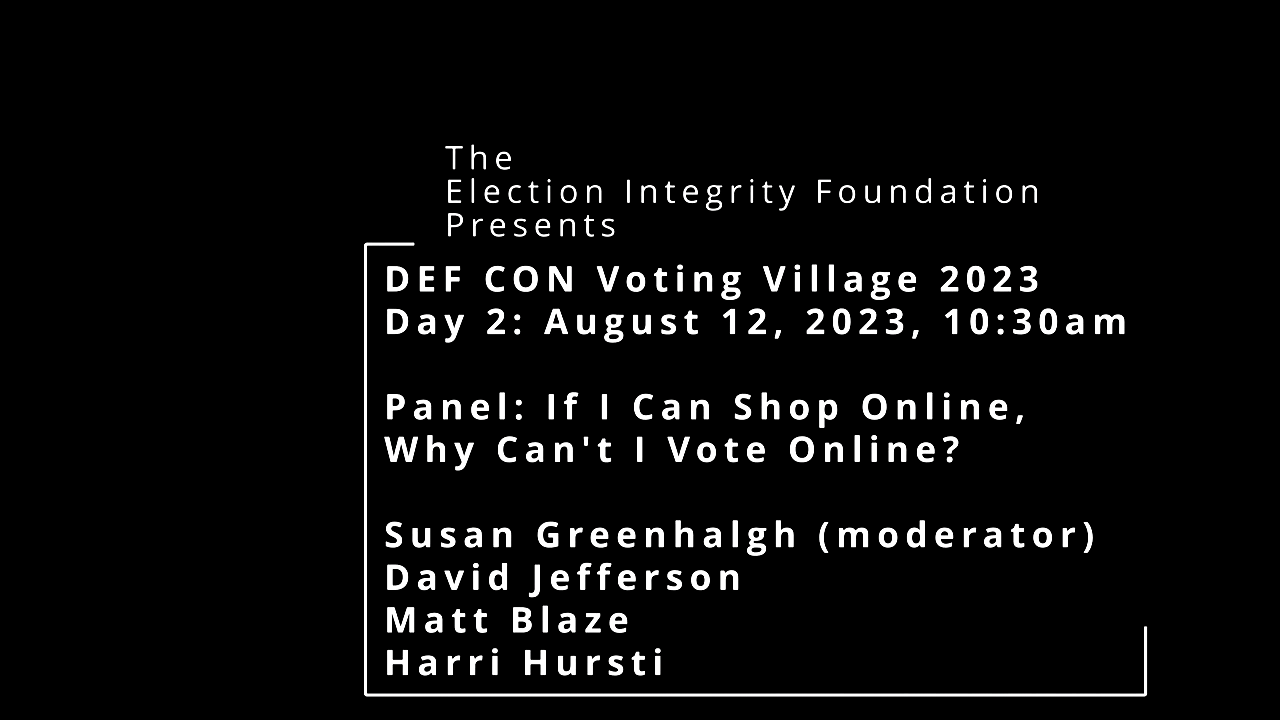

There was a DEFCON Voting Village panel «If I can shop online, why can’t I vote online?» which I found extremely important to read or listen to. Not just for me, in fact, for anyone talking about electronic voting. Here is a transcript for those who prefer reading (or searching for keywords).

Of course, a link to the original video may not be missing, for those who prefer to watch or listen.

Editorial remarks

The transcript has received minor editorial changes: Placeholders (“uh”, “you know”, …), repetitions, self-corrections, etc. have been removed in order to improve readability. Text in angle quotes («…») would be indirect speech in a written text; from the context, it is meant to be a summary/rephrashing of someone else’s statement, illustrated by a change of tone, not as a direct quote.

Chunks that are related to the organization of the panel and that are unrelated to the content have been removed for clarity.

Bold text and section headings have been added by me to help you navigate the arguments or point out what I believe are important take-home messages.

But now, let’s switch to the transcript:

Introduction

Susan Greenhalgh (00:08): I’m Susan Greenhalgh, I’m the senior advisor for election security at Free Speech For People. We are a national nonpartisan not-for-profit legal advocacy organization that works protect elections and democracy for all the people. We have a Proprogram which focuses on Election security and I’ve done a lot of work on internet voting for over 15 years studying the policies and practices and written several reports on it. I’m here to talk about this issue with our esteemed panel.

First starting with David Jefferson: Dr David Jefferson, who is a researcher from Lawrence Livermore Laboratories, retired. In 1999 to 2000, he was the co-chair of the California Secretary of State’s task force on internet voting. He’ll talk a little bit more about that. He was the one of the co-authors of the peer review that was done on the Department of Defense’s SERVE internet voting system in 2004, which ultimately resulted in the Department of Defense canceling the project. and he can talk a little bit about that. It was a 22 million dollar project that was ultimately shut down and he’s been writing, speaking, and testifying in opposition internet voting ever since. So that’s David.

Next we have Matt Blaze, professor at Georgetown University School of Computer Science and Law. He is also co-founder of the Village and he’s been working in election security for two decades and especially interested in the impact of complex software systems on security and reliability.

And Harri Hursti, also co-founder of the Defcon Voting Village. He is the OG in election security reviews, famously conducting the Hursti Hack back in the 2000s. He also was part of a team that reviewed the Estonian online voting system for security and traveled to Estonia to present the findings to people there.

So, we have an incredible panel and I will turn it over to David.

David Jefferson: Problem space

David Jefferson (03:12): So, first let me give you a summary up front of where I’m coming from. That which is, that it isn’t possible now or in the foreseeable future with any combination of technologies that we can envision today to secure an online voting system and so thus we shouldn’t be instituting internet voting anywhere in the U.S and we should really stop using it where it’s in use today.

National security

Voting of course is a national security issue: The legitimacy of democratic government depends on voting being secure and and open. So we really cannot open our voting systems to the to the various kinds of threats I’m about to describe to you, many of which would open our elections to manipulation by Foreign actors.

So let me talk about what internet voting is first of all. What we mean by that is any voting system in which voted ballots are transmitted over the Internet; maybe one hop of the communication is just over the internet, but if it’s if voted ballots are ever transmitted over the internet in the course of running an election, it’s an internet voting system. It doesn’t matter whether it’s by email or fax or web or mobile app: Any scheme, doesn’t matter what the protocol is, if it’s transmitted over the Internet, it’s going to be vulnerable to the kinds of threats I’m about to describe.

Attack vectors

So let’s talk about those threats. What are the threats that we’re talking about? There are many of them.

- The first one is authentication related threats. When you vote online, of course you have to identify yourself, so that you can be checked that you’re registered and that you haven’t already voted. So you have to actually identify yourself. That will have to be done online also and an attacker can can mess with that system, so that it makes it too difficult for people to authenticate themselves and they get disenfranchised; or too easy for people to authenticate themselves and phony voters can vote. So authentication threats, number one.

- Number two and perhaps the most insidious is client-side malware. You’re going to be voting from some device—a phone or a PC or other mobile device—and that device might be infected with malware. And that malware might have the purpose of interfering with your voting, either preventing you from voting or modifying your votes before your votes even get out of the device. Before they’re encrypted for transmission, your votes can be modified: You wouldn’t know it, the election officials wouldn’t know it. That’s a profound problem, the client malware problem.

- The third problem: The third kind of attack would be network attacks; attacking routers or DNS or other parts of the internet infrastructure. Where even if your ballots are transmitted, in progress, they can still be stopped or redirected or otherwise interfered with.

- There are spoofing attacks, where you’re tricked into voting to an incorrect site: A site which may look like the real site, but which is not. And and you think you voted, but you didn’t, and you don’t know whether your vote was transmitted or modified or just thrown away.

- There are denial of service attacks, where the server that receives votes is overwhelmed with a lot of of fake ballots, sent to it by an attacker. It’s so overwhelmed that the service slows down. It may slow down to the point where voters get timeouts and they can’t vote at all; or the server just crashes.

- There are server penetration attacks, where an attacker actually gains control remotely of the server that’s accepting the ballots and when he gains control he can do anything he wants.

Many of these attacks can be Insider-aided, but insiders would include election officials and programmers and so on. There are many variations of all of these attacks.

No strong defenses now, …

Now, there are no strong defenses to most of these attacks; there just are no strong defenses. There are ameliorations, there are ways of handling certain special cases of these attacks. But there are no general solutions with technology that we have today.

They rest on some profound problems in computer science which Matt is going to tell you about in the in the next talk. These are the same threats that we encountered 25 years ago when I was the chair of the California Secretary of State’s Internet Voting Task force and they’re why we recommended that California not Institute internet voting in 1999.

… and probably never

These threats haven’t really changed materially in the last 25 years and they may not change materially in the next 25 years; they are that intractable! Now, the problem is that all of these attacks that I mentioned can be automated and scaled up to massive scale. Depending upon technical details of the architecture of the voting system, the attacks can come from anywhere on Earth, including rival nation states or our own domestic partisans.

Attack detection/identification

Successful attacks may go completely undetected; but if they are detected, they may be completely uncorrectable without running the election over again.

The perpetrators of the attack may never be identified. But even if they are identified, they’re likely to be out of reach of U.S. law—as the 12 Russians, who are under indictment for interfering with the 2020 election are out of reach of U.S. law.

So the problems with Internet voting are profound and I’m going to now turn it over to Matt so he can talk more about that subject. Thank you!

Matt Blaze: IT security

Matt Blaze (09:27): So thanks, David! I just want to expand on what some of the stuff that David was talking about. He mentioned fundamental problems. And as a scientist or as an engineer, when somebody says, “that’s a theoretical problem,” we understand it to be different from when the general public uses the term “theoretical problem”.

A theoretical problem in normal life is one you don’t really have to worry about; a theoretical problem in science and engineering is the worst possible kind. Right, it’s the kind that is fundamental to the system; that it’s something that you cannot do anything about without either changing the assumptions or compromising on what the requirements are.

Fundamental, unsolvable problems

And there are two sets of fundamental problems:

- The first set of fundamental problems are computer science problems and all of the problems in voting—in building a secure voting system—that we encounter from an engineering point of view, are problems that actually were around before voting was an application. People were even considering there is a fundamental theorem in computer science that essentially says, “it is impossible to compare a program with its specification and understand whether it meets it”. And this is not a problem that we simply haven’t worked hard enough to try to solve; it’s a problem that we know that we cannot solve. We will never be able to solve it!

And what is the implication of that, is that general purpose complex software can never be assured to be completely correct. Now, that mostly doesn’t bother us for all sorts of applications of computing that we rely on for many things. In fact, the title of this panel «I can bank online; why can’t I vote online?» is an example of that.

We rely on the same flawed computing systems for things like banking, so, why is it we’re able to get away with it? And the short answer is: We don’t. Right, bank fraud is enormously common; right, banks are robbed online all the time; there are identity theft and so on constantly. - The difference is a second set of fundamental problems which is the voting application itself has a set of incredibly stringent and in fact somewhat contradictory requirements for building a voting system.

One of them is that your vote must be anonymous and it must be anonymous to the point where you can’t even voluntarily prove who you voted for. And that requirement exists to prevent people from being able to be coerced into voting a particular way or being able to sell their vote. And there’s a long history—even in the United States, prior to that requirement existing—of people having their franchise coerced away from them, because it’s possible to tell how someone voted.

Banking transactions don’t have that requirement. A banking transaction is reversible. If money disappears from your bank account, it’s possible to be made whole again; but if your vote is changed, after it’s been cast, we don’t know whose it was. And you have no way as a voter of proving how your particular vote was cast in order to be able to correct that. And if that changed, you’d be able to prove how you voted.

Impossible reliability

So we have these two sets of fundamental problems clashing with each other: The first is, we don’t know how to build systems that are reliable enough to avoid problems like this; and the second is, voting requires us to build systems that avoid problems like this rather than correct them after the fact. And this combined with the fact that an online voting system requires using complex computer technology means that this is a problem that we won’t be able to solve no matter how hard we work at.

It’s not that we’re just not very smart, it’s that these problems are beyond human capacity.

Accepting the risks?

Where that leaves us is,

- we have to recognize that online voting is intrinsically very risky,

- that it will lead to elections that we will never be able to satisfactorily show were conducted without fraud, without hacking, and that the outcome is genuinely true.

And that will always be with us when we do it that way, unless we relax some very important requirements of voting systems.

So, by the way, I’m not the only one saying this. There was a report from the National Academy of Sciences called “Securing the Vote”, where the top experts in the field got together and produced what’s called a “consensus report”. It essentially makes a very strong statement: «This is something we do not know how to do» and recommends against it wholesale.

Conclusion

So, those who propose online voting systems are essentially proposing something that [according to] the consensus of scientists is impossible.

So, we should understand it in that context. So, thanks!

Harri Hursti: False promises

Harry Hursti (15:35): So internet voting is a whack-a-mole. It keeps on coming back and the argument is very often, say, well, we have this excuse: Shall we do just a little bit of Internet vote?

There’s two reasons why that’s not a good idea:

- First of all, all the votes are one pool. The idea that I can vote insecurely myself, and that wouldn’t disenfranchise other voters, is a logical fallacy. Because if there’s only one result and if I’m choosing to make my own vote insecure, I’m also making everybody else’s vote vulnerable.

- But there’s even more profound reason. A lot of nations, including the United States and a lot of states in the United States, but other nations have the same principle: that all voters should be voting with same method. So, once you are enabling the door that let’s have a little bit of Internet voting, the next step is to say, now everybody has to vote with internet voting because we cannot have separate methods. The common ways we are hearing always to give an excuse: What are the special groups who need to vote over the internet?

- And one of the these in America is called UOCAVA Voters, Uniformed and Overseas Voters Empowerment Act [Transcriber’s note: Merge between UOCAVA and MOVE]. So, they are mainly the boys and girls in the military and who have a problem of getting the ballots done on time; however, this same problem is everywhere else in the world. And the other part is why UOCAVA is—or military voters in general are—a very good target for saying, “let’s do internet voting,” because in a lot of nations, military voters are not guaranteed to have secret ballot; it’s a best-effort basis only. So military voters don’t enjoy the same legal protections as the general public. And that also enables you to have a little bit more relaxed voting system, because you don’t have to guarantee secret ballots.

- Another group is a very powerful lobbying group: The disabled voters and especially print disabled voters, so people who cannot read, cannot write, cannot hold a pen in their hand. There are a lot of devices, calling for example ballot marking devices, which are designed to access. But the idea is: Okay, well, let’s do that at home! Again, this whole path leads to a dual language, where a constant attempt is to call the voting not “internet voting”, but instead of calling it to be “electronic return of your ballot”. It’s the same thing. But the idea is, this is the way we sell the idea without getting into the trap of informing people that this is the bad idea again, internet voting.

Estonia

Internet voting has been claimed to be successful in Estonia. I went to Estonia with the professor Alex Halderman and a couple of other folks. We took a look in the system and it was a fairly decent high school project; that was the quality of the code.

However, there was a lot of interesting things in operations. For example, they rented the servers every year separately. So, from supply chain point of view, this one agency is renting three computers: That’s your target! The lowest bidder and you can poison all you want. There were a lot of designs in that area.

For example, they publish a video where a the code is signed cryptographically, so that the voters will know, this is an honest code. And they claim that this computer, where the video was taken, has never been connected to internet. But it had a µTorrent [Transcriber’s note: A BitTorrent Internet download software] and pirated movies and pirated films and online poker on the screen. So slightly suspicious that it might have been an intern.

Finland

In Finland, we tried internet voting or online voting. It was Kiosk Voting—but a system which can be used for internet loading too—in Three Counties and it was demonstrated that three and a half percent of the votes were lost and hence the election had to be reconducted, because three and a half percent in a what you call the Jefferson counting method means that it’s absolutely certain the last candidates in the city council will be [awarded to?] the wrong people.

«Young voters!»

The common excuse also is to claim that we need internet voting to activate young voters, young people who like mobile phones.

Estonia is a brilliant country from the point of view that they published age brackets. And when you look in Estonia, you see that the fastest growing group of Voters online is over 65 and the young voters are rejecting the idea of Internet voting. The same was [experienced] in Norway, so that the actual government public data doesn’t support the common wisdom that young voters would be activated by using internet voting.

«Understandable, verifiable»

Last but not least, I want to touch a very big topic. For example, in Europe and Germany, a lot of democracies have a rule that common person has to understand how votes are counted; and have to be able to verify the vote counting process with no special tools and education. Common man’s common knowledge has to be enough. Now, we are proposing very complex ideas like homomorphic encryption, blockchain, …

The joke in US is that the average age of poll workers [gets] one year older every year, because we don’t have enough young people coming to be a poll worker. But until we live in a Star Trek universe, where teenagers are casually talking about quantum mechanics: Who is going to be explaining to a 70 year old normal person, how homomorphic encryption works?

And in this today’s world, how could anyone believe that you could ever be getting normal people to accept these complex ideas, that even most of the experts don’t know how it works?

So let’s keep it simple. Thank you!

Susan Greenhalgh: History

Susan Greenhalgh (20:10): After hearing all of that, I’m guessing everyone probably thinks, «who would ever want to do internet voting for public governmental elections?»; but unfortunately, right now 32 states permit some subset of voters to vote online either by email, fax, or some sort of online portal. And there’s a lot of ballots coming back online! In the 2020 election, there were over 300 000 ballots cast online; and in some states with small margins, there were a significant number of ballots cast online. And this is a problem, because those ballots we know are not secure and they can’t be audited.

Trying to create

So, I want to talk a little bit about the policy in the history of how we got here and how it’s playing out today to understand our situation. As I mentioned in the intro, back in 2004, David was part of a security study that examined a system that was being put together by the Department of Defense to a military and overseas voters to vote online.

This was something that Congress tasked them to do this. They built a system, had a peer review of the security. The peer review said, this is not secure, you cannot ensure the legitimacy of ballots cast online. So the project was scrapped.

Standards first

Congress turned around and said: Okay, we’ll have NIST—National Institute of Standards and Technology—develop standards for a secure online voting system and then we’ll have the Department of Defense build to those standards. So NIST spent the later part of the 2000s and early 2010s studying the problem, writing several reports, and they came to the conclusion—that the scientists have all come to—that there’s this broad scientific consensus that these problems are really not solvable with the security tools that we have today.

And they wrote a statement saying, we don’t know how to write security standards, because we don’t know how to do internet voting securely. It’s not yet feasible, so we we’re not doing it. So Congress said «okay» a couple years later; because Congress moved slowly between 2014 and 2015. Congress repealed the directive to the Department of Defense to build an online voting system; essentially taking the federal government out of it.

We often hear: «Why isn’t the federal government studying it?» The answer is: They already did; asked and answered. So in the subsequent years we’ve seen more reports come out; in 2018, the National Academy study came out that Matt mentioned. There’s been numerous academic studies, there’s been some states have done their own studies.

Time and again, when the computer scientists and the security experts look at the problems, they realize that voting is not something that you can apply today’s security tools to, in a sufficient way to secure it. So, we’ve never come up with anyone that says, «Here this is a secure way to do it from a scientific perspective».

Policy before Possibility

Yet, in that early 2000s period of time and even the late 90s, there was a reasonable expectation that we were going to have a secure online voting system from the Department of Defense. So States passed laws to allow electronic ballot return. By 2010, I think 29 or 30 States already had electronic ballot return laws in place. So that was before NIST came up with their statement saying, «we can’t write security standards for this», and before the bulk of the scientific research that’s so conclusive had come out by. So, in the mid 2010s, we’d seen a kind of a slowdown in the movement for online voting; but now we’re in the middle of an aggressive push once again to have people vote online and that’s coming mainly from two places:

1. Bradley Tusk

First, there’s a guy named Bradley Tusk who is an Uber multi-millionaire: Made a bunch of money for Uber and he helped change their policies. Not a tech guy, he’s a policy guy. He helped change state laws to allow Uber ride share policies around the country. He also was responsible for changing state laws to allow sports betting on the FanDuel app. So he knows what he’s doing as far as changing state laws. And he’s decided that he’s going to save American democracy by getting everybody to vote on their phones by 2028, he said that on his podcast. He has also said, that he will do anything unethical—short of committing a crime—to get everyone voting on their phone. So, he’s hired lobbyists, he’s got public relations people, and he’s introducing bills in different states around the country to allow people to vote online: Starting with subsets of military and overseas voters for states that don’t already have it, and then to expand it to voters with disabilities, to expand it to First Responders who may be displaced, and then ultimately with the goal of getting everybody to vote online.

Despite Federal warnings

One of the most definitive scientific studies that we saw—or I shouldn’t call it a study, it was a risk assessment, that came from the Department of Homeland Security CISA, FBI, NIST, and EAC in 2020, which warned States: «You don’t probably want to do this, because those ballots will be high risk of compromise, manipulation, deletion, or privacy violations. Any ballots cast online via any method, even with security tools in place.»

State legislation lobbies

So even with this security, all this guidance coming from the federal agencies: Those federal agencies can’t go into the States and lobby. They put out their risk assessment, hope the states look at it. Instead, it’s left to organizations like our organization. We work with Verified Voting, with Brennan Center, with Public Citizen. These are all groups. We are very deeply committed to ensuring access for all voters. We—my organization—actually takes legal actions to ensure people’s access to the ballot. But we also want to protect that ballot and make sure that the election is secure. So that’s why we are going in and raising these security concerns in the state legislatures and trying to keep States from introducing more bills to spread online voting.

In the last year and a half, we saw bills introduced in California, Washington, Maryland, Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Georgia, New York, New Jersey, and Washington D.C.

That’s one aspect of the push for online voting.

2. Vendors

There’s another aspect that comes from the vendors. Because this is an industry that is not regulated at all, the systems that are being sold commercially don’t undergo any sort of public testing that anyone else can review. The vendors make claims of security or claims about the way the system operates that are unfounded, baseless. Our organization has written letters to Attorneys General, arguing that these could constitute false claims in deceptive marketing and could be actionable and asking for investigations. But there’s nothing to counter it, other than us bringing up the other side of it. So the vendors are also lobbying in state legislatures and promising State lawmakers that these systems can be secured.

And that’s another aspect of it.

Confidence in elections

So this is an ongoing problem that we’re going to continue to see, because of these two forces pushing online voting at a time when we really need to have auditable systems, transparent systems, secure systems, that we can ensure that all people can have confidence in the results of an election and not expand an system that we know is insecure.

«Theranos of voting»

Internet voting has been globally referred to as the «Theranos of voting» and I think that’s actually a very apt analogy. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the story: Theranos is the blood company that was founded that went to a billion dollars; and they were going to take a tiny pinprick of blood and be able to run a complete screen of every task that you could ever possibly need and know your entire health history. And it would be cheap and everyone would be able to do it at CVS or Walgreens.

And it was a great idea, who doesn’t want that? But the problem is: The science didn’t let you do it! You needed more blood to be able to run certain tests. The blood needed to be centrifuged, and separate out the cells, and reagents put in there. You can’t do it all, but the idea is so great, everybody wants to do it!

Yes, it would be really great if we could all vote on our phones, but the science isn’t there!

So I’m going to wrap with that and and we’re going to go to questions.

Q&A

Auditing?

Susan Greenhalgh (31:01): David, I was speaking about the importance of auditing elections, especially that everyone should have confidence. We don’t want to just trust elections, we want to verify elections. How can you audit an online voting system or can you audit an online voting system?

David Jefferson (31:32): You hand mark the ballot and there is no question that the ballot actually reflects the voter’s intent. That hand marked ballot becomes a contemporaneous record of the voter intent. So that if those ballots are later counted by machine—and the software in those machines is full of bugs and is full of malware, and so the counts are wrong as produced by a machine—you can always go back, in fact, you should always go back to the original hand-marked paper ballots and audit the machine results using an RLA (a risk-limiting audit), for example, as was discussed apparently yesterday.

And therefore you can determine that the machine counts were wrong and you can correct the outcome of the election.

Now, with any kind of online voting system, if you are voting from your phone or your personal computer, there is no indelible contemporaneous record of what the voter’s actual intent was. There is no record from which to audit the election.

So, it’s really not possible to audit an online election and that’s just another reason why we shouldn’t be doing it.

Digital «voter-verified paper ballots» aren’t

Susan Greenhalgh (33:16): One of the things we see the vendor say, is that «we produce a voter-verified paper ballot, our system isn’t online voting, it isn’t internet voting». Oe of the the CEOs of one of the vendors told a radio show that «We don’t use the term “internet voting”, because it’s a loaded term; we say “electronic ballot returns”.» So it’s a little bit of this smoke and mirrors.

And that they produce a voter verified paper ballot: Well, a lot of times, the digital record is sent to the elections office and then it’s printed there. But obviously that paper ballot has never been verified by the voter, because it’s the digital record that was sent. But to say, «it’s a voter verified paper ballot», is highly misleading at best, so you don’t have a voter verified paper ballot to audit the election.

Eliminating vote secrecy?

Audience Member (34:16): You folks were talking about the kind of combating requirements of a secret ballot and a technically secure ballot. I vote for Mickey Mouse every year, I don’t care who knows that. From a purely technical perspective, if you omit the requirement of secrecy, does online voting become much more viable?

Matt Blaze (34:37): Sure, all sorts of problems get easier, if you reduce the requirements. The requirement for a secret ballot doesn’t exist just because a bunch of technologists said it should. The requirement for secret ballot evolved over centuries of U.S law; and centuries of experience with fraud in democracies, based on coercing votes from people.

We could—as a society—decide to eliminate the secret ballot and maybe we decide that we want to. But I think a poor reason to eliminate the secret ballot is simply to accommodate some future voting technology, that finds it an inconvenient requirement.

I think it’s very important to understand here: These requirements didn’t come from us, these requirements are not requirements that the technologists invented. These are requirements that society has decided are important properties for voting systems. We can discuss whether those requirements are good or not, but that discussion had nothing to do with technology, it’s a democracy requirement.

Perpetual motion machines

When I hear about internet voting, I find it helpful to substitute in my head «perpetual motion machine». If we had perpetual motion machines, it would be great! It would solve our energy problems.

Everybody agrees perpetual motion machines would be terrific! Unfortunately, a bunch of killjoy physicists tell us that we’ll never be able to have them. If you believe the killjoy physicists, it would be a bad idea to create policy on the assumption that we’re about to build a perpetual motion machine, because we’re really not. And internet voting has many, many of the same properties there.

Praise for secret ballots

David Jefferson (36:42): I want to praise the secret ballot requirement: The secrecy of the ballot is the strongest defense by far we have against voter coercion, vote retaliation, and vote buying and selling. Without the secret ballot, our elections could be irredeemably corrupted by those effects.

Internet voting is racist

Audience Member (37:10): I have more of a comment that I’d love to get our moderator’s response on here. What really worries me more than anything about online voting is much more lower tech, actually, it’s that if it goes large scale it’s subject to phishing attacks. You could have very large-scale voter suppression with fake emails coming from secretaries of State, apparently, and you go and you lose your vote and maybe you get your identity theft too. Now, phishing campaigns can be just 19, 20 % effective; targeted they can be 70 % effective and who’s going to get targeted in a voter suppression campaign? The same people who always get targeted: Communities of color! So, I think this whole issue very quickly becomes a racial justice issue, honestly, and that’s that’s not even getting into the stuff you all have been talking about, that I firmly agree with.

Susan Greenhalgh (38:13): My comment is: I agree. I don’t have much more to add that was very well put!

Biometrics

Audience Member (38:21): Just a quick question regarding authentication and biometric data: So can your team speak to the benefits of that? I know that the TSA for example is using biometric data for authentication purposes for international travel; comparing your passport photo to your face while you check in. Obviously, having biometric data stored by the government maybe isn’t the best idea; you could do something like hashing or something different like that. But can you speak to the advancements of biometric data and how they pertain to online voting in the future?

Matt Blaze (39:00): There are two unfortunate properties about Biometrics. The first is they are tied to you as an individual; you can’t change them if they’re compromised. So if something happens to your biometric data and other people learn about what it is, they know it and you’re stuck. That means that effectively supervised biometric authentication—you go into the kiosk, there’s a guard, you put your fingerprint on a reader—might be okay, because they know that you’re not bringing some equipment in, to fake what the fingerprint is. But unsupervised biometric authentication—I’m using my phone, it reads my biometric, and sends that data somewhere—is something that’s always going to be subject to compromise. So Biometrics solve some problems for in-person authentication that work very poorly in the online context.

Vote by phone isn’t secret

Audience Member (40:12): I think another issue that isn’t really considered, is the fact that, for instance, if Bea is going to vote with her cell phone and she’s asleep, I can just pick up her cell phone, unlock it with her face and vote on it. Or Bob over there wants me to vote for Pinkie Pie, so he gives me a thousand dollars to go vote for Pinkie Pie. We still have that problem in our regular elections and those are small little votes. But there’s no privacy.

If you have a partner that’s very controlling and they’re trying to force you to vote for somebody: When you walk into that voting booth by yourself and you close that curtain, you can vote for whoever you want. You lose that a hundred percent when you do online voting and vote by phone or any of this. Great for American Idol, not great for elections.

Remote (postal) voting

Audience Member (41:19): I have a general question about remote voting which is not electronical, such as postal voting, which is used in many countries to support for example disabled voters or voters who are otherwise unable to go to the polling station. And postal voting has many risks of the kind that you mentioned, such as the risk of coercion or the risk of not knowing that the ballot that arrived was actually marked by a legitimate voter. So given all this, what kind of secure enough options would you recommend for remote voting?

Matt Blaze (41:50): It’s important not to confuse online voting with the general problem of remote voting. Remote voting exists everywhere in the United States at least as a special case for absentee ballots: People who can’t travel and so on. It’s generally done on paper and by mail.

That has some of the same problems as online voting, but not all of them. It leaves us with the one-on-one coercion problem, that if you’re sent a paper ballot, it is possible you could be coerced by a partner or an employer to vote in a particular way. But that has to be done on a retail level, ballot by ballot.

In an online voting system, that same type of compromise can be done centrally: A piece of malware, that’s spread by a phishing or any of the other ways that malware spreads, can be used to wholesale compromise many, many different ballots.

So, my suggestion is that to accommodate voters who can’t travel, we stick to the paper-by-mail method and not introduce methods that also add the wholesale fraud and wholesale abuse vector. But even by mail, voting does compromise some of the properties of the secret ballot; and we have to be very careful when we scale that up.

Susan Greenhalgh (43:37): I’ll just add that there have been solutions that have been implemented: When the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment Act was passed, it required that all Counties or States send ballots to Military and overseas voters 45 days before the election. It also stipulated, that they had to make the option available to send the blank ballot electronically. Blank ballots can be sent with reasonable acceptable security electronically, because they don’t have the vote, they don’t have the secret valued piece of data, on them; everybody knows what’s going to be on the blank ballot. So, you get your blank ballot in 45 days and then still have 45 days. The military have access to expedited free postal mail return that is provided to everyone in the military.

I mentioned there’s 32 states that currently allow electronic ballot return, 18 that do not. There are several states that don’t allow electronic ballot return, that have higher rates of participation for military and overseas voters, because they have robust communications in place: They’re making sure that they get the information to those voters. So, I don’t think that we can make a correlation that electronic ballot return is going to increase participation for those voters based on that information.

Voter outreach

Audience Member (45:03): Military ballots and voting is always kind of interesting on all the campaigns I’ve worked on. Generally, each county is autonomous and how they vote in it. You’re talking about military and state. I’m really a novice, I really don’t know what I’m doing on this one. So, you’re saying the states have better things in place. So, how does that work with the counties being autonomous and how they do their voting?

Susan Greenhalgh (45:45): It actually depends State-by-State, because some States run their UOCAVA outreach to those voters or military and overseas. The outreach of those people at the state level and some places do it at the county level; meaning that the county officials have to email the ballot or send the ballot to the people; or some places, they do it from the state level. So it really depends on the state: You have to go State by State.

Ballot marking machines vs. secrecy

Audience Member (46:20): I think it’s important for people to be careful not to generalize your personal experience of voting and think that’s how it is throughout the United States. It’s easy to make blanket statements that don’t apply. So, for instance, with respect to voting by mail: If you live in the state of Georgia, the only way to be able to do a hand-marked paper ballot is, if you vote by mail. The only way to have ballot secrecy is, if you vote by mail. Because, if we go into a precinct, we have ballot marking devices that are huge. They’re upright, they’re lit up, and anyone can see how you’re voting. So if you want ballot secrecy and hand-mark paper ballots in the state of Georgia, you have to be able to vote by mail. And the other thing to be aware of in the state of Georgia, is that the Secretary of State controls all counties. So, we’re required to do everything the same way throughout the entire State; it’s not county-by-county decisions. So I just want to caution people: Don’t generalize based on your own experience, because across the United States there are very different circumstances.

The transcript ends here, but some relevant information follows, for those wishing to dig deeper.

Related work

U.S.

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine et al.: Securing the Vote: Protecting American Democracy, 2018.

The «Consensus Report» mentioned above. - Kim Zetter: US government plans to urge states to resist ‘high-risk’ internet voting, The Guardian, 2020-05-08 (or 2020-05-09 CEST).

Report on the DHS risk assessment. - Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA): Election Infrastructure Cyber Risk Assessment, 2020-07-28.

Enumeration and quantification of risks related to internet voting; also mentioned above. - Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA): Risk Management for Electronic Ballot Delivery, Marking, and Return, undated (but before 2020-05-08).

Essentially a summary of the risk assessment above, referenced in the Guardian article; scanned, labelled as “draft”.

Estonia

- Märt Põder: Do voting machines dream of digital democracy?, 2023-10-17.

Slides of his presentation in Zurich on the Estonian electronic voting system (including: how he might have stolen the election, but didn’t; that results differ greatly between internet and paper votes.) - Estonian Cyber Security News Aggregator: Cyber Security Newsletter 2023-10-12 (i-voting / RK2023).

Extensive list of the problems during the Spring internet voting in Estonia. - Märt Põder: Should e-voting experience of Estonia be copied?, 37C3, 2023-12-30.

Märt’s presentation at the 37th Chaos Communication Congress.

Switzerland

- James Walker: Swiss Post puts e-voting on hold after researchers uncover critical security errors, The Daily Swig, 2019-04-05.

Sarah Jamie Lewis and others discovered bugs hidden deep in the hard-to-understand cryptographic core of the Scytl/Swiss Post eVoting system. (As of 2023, it is again in use in Swiss elections/votes. Many more articles not available in English.) - Patrick Seemann: eVoting: No risk, have fun?, DNIP, 2023-09-04.

According to the Swiss eVoting risk assessment, the risk is now lower. Without any substantial changes to the system. A critique (in German 🇩🇪).

Technology

Homomorphic Encryption and Blockchain are mentioned here (and elsewhere), as potential solutions to Internet voting aka eVoting. If you want to understand these technologies, here are some pointers:

- Marcel Waldvogel: Post Quantum and Homomorphic Encryption made easy, 2023-02-23.

Toy versions of these topics explained, so that everyone can have a basic understanding. - Marcel Waldvogel: Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Blockchain, 2022-04-09.

Blockchain technology explained. Here, the link to my statement about electronic voting and blockchain. - Marcel Waldvogel: Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Blockchain: An Overview.

Overview over my articles about Blockchain and related technologies.